I am imperfect. We all are. I am a product of my past. But my future is hopeful. As I look at my life up until this point, I see that conviction has connected me to a life of purpose. You can see me, but you cannot see my soul. I’m living on purpose and I know where I want to go.

I believe it is important for each of us to write down the things we want to accomplish, the people we want to meet, the changes we want to make for ourselves and the world around us. Here’s a look at what I hope to accomplish in 2020:

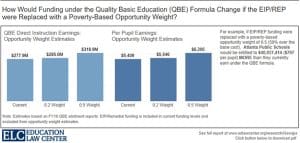

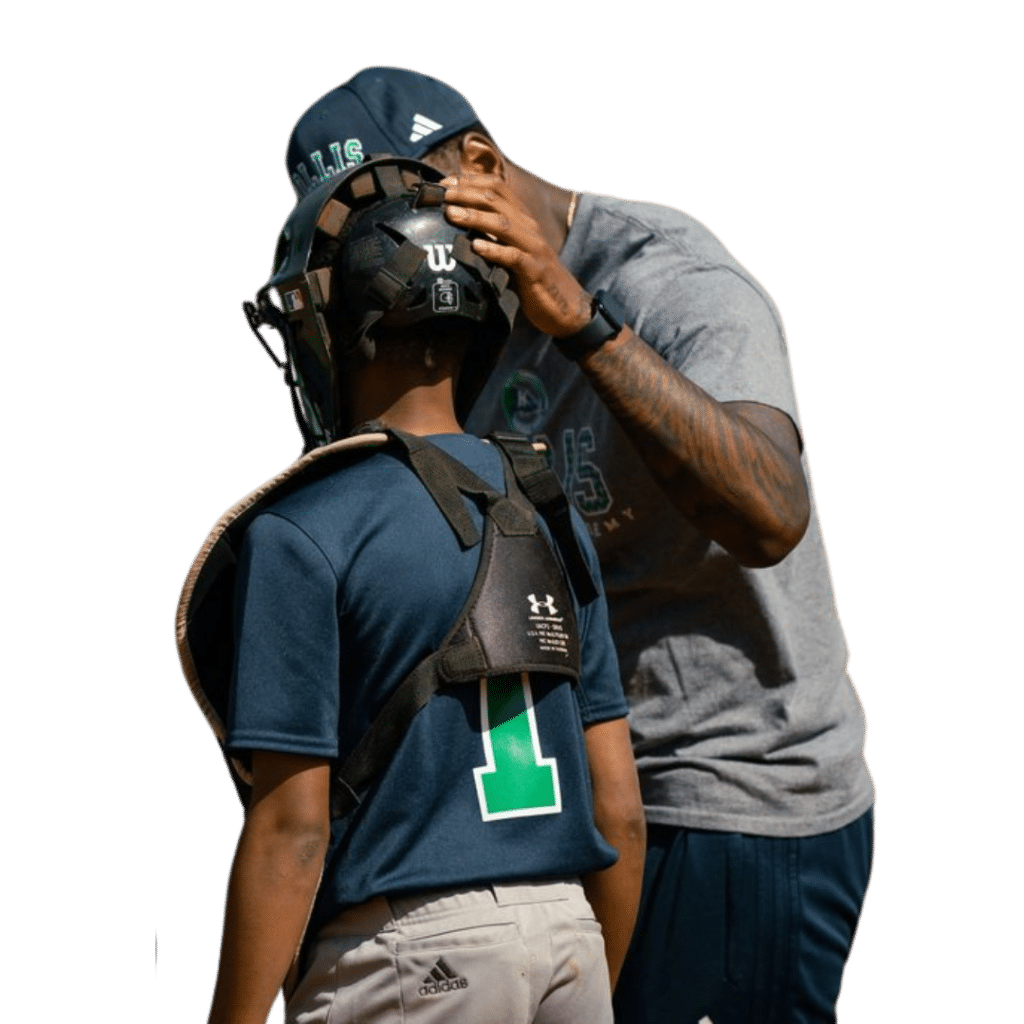

2. I want the new Atlanta Public Schools Superintendent to respect the culture of sports as co-curricular rather than extra-curricular.

3. I want the Atlanta Public Schools Board of Education to propose mandatory African American history classes within all middle and high schools in all Atlanta public schools.

4. I want Atlanta citizens by the hundreds of thousands to be aware that we are not yet a “City too Busy to Hate.”

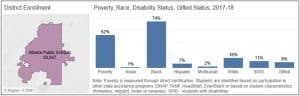

5. I want Atlanta citizens by the hundreds of thousands to be aware that our state has a problem being in the top third of non-profits in the US, yet for the second year in a row, “Atlanta is the capital of U.S. inequality,” according to a Bloomberg analysis of large American cities with a population of at least a quarter-million.

6. I want to vet 20 volunteers for L.E.A.D. who can serve our Ambassadors by being a present, being present and being a partner.

7. I want the Braves to win the World Series and the Falcons to win the Super Bowl.

8. I want to read at least 20 books.

9. I want to start writing my second book.

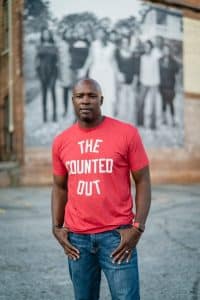

10. I want the L.E.A.D. Ambassadors book, “Voices of the Counted Out” to sale more than 50,000 copies.

11. I want at least 100 fans at each of our spring L.E.A.D. Middle School Character Development League games. The MSCDL schedule will be posted by Feb. 1, 2020.

|

| L.E.A.D. Ambassadors along with Chief Patrick Labat |

13. I want to do another Spartan Race with the L.E.A.D. Ambassadors.

14. I want to run in the Peachtree Road Race with the L.E.A.D. Ambassadors.

15. I want to launch a capital campaign to raise funds for the L.E.A.D. Center For Youth.

16. I want Chief Patrick Labat to be the next Fulton County Sheriff.

17. I want to be wise and courageous while inspiring others to do the same.

18. I want to remain healthy spiritually, physically, mentally, emotionally, financially and relationally.

19. I want to remain unwaveringly committed to using my wealth of social capital to help tens of thousands of marginalized families in Atlanta.

20. I want to remain unwaveringly committed to being regarded as man of God who is aspirational rather than using bravado to become successful at the expense of others.