For all intents and purposes, I’m a Grady Baby. I was born in poverty in the inner-city of Atlanta. My mother, Gail, was 16 when she gave birth to me. She is the epitome of resilience and focus. My father, Willie, has always been in my life, and still models the qualities of commitment and discipline for me.

When I was a kid, young African Americans like me grew up hearing rhetoric like, “You could never be an athlete and intelligent at the same time.” Looking back, they were dumb jokes. What was real was the notion that while education could never be taken away from us, sports could.

As I grew older, I saw the pipeline of employment riding through the white community—one that helped young people prepare for the future. It was different for me. I was blessed to be on the right team, at the right time. I was coached by Emmett Johnson, Sr., who at the time was chairman of the Atlanta Public Schools’ Board of Education. I was also coached by Joshua Butler, a respected art teacher at Benjamin Mays High School. My family was not among the middle class, but my coaches were.

Playing baseball helped me build good habits, confidence and discipline. It shaped me into a community leader, teaching me how to strive for a goal, handle mistakes and cherish growth opportunities. Playing for Coach Johnson and Coach Butler gave me access. Through that access, I felt a sense of belonging to my birth city, Atlanta. I felt a sense of investment.

I dreamed of escaping poverty by entering the middle class.

My late mentor, Charles Easley, told me that ‘back in the day’, you did not become a man until you were allowed to play baseball. It was the principle he grew up under. Families would leave church and immediately head to the park to watch men play baseball. Sports like football and basketball were not even options. The University of Georgia recently uncovered the oldest known film footage of African-American baseball players. The footage is mesmerizing.

“I felt unhappy and trapped. If I left baseball, where could I go, what could I do to earn enough money to help my mother and to marry Rachel? The solution to my problem was only days away in the hands of a tough, shrewd, courageous man called Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers.” — Jackie Robinson

Atlanta is recognized as a world-class city. That would have never happened if it did not prove that it was a “city too busy to hate.” The transformation was set into motion when the Braves relocated here from Milwaukee. In fact, because of Jim Crow segregation laws, the Atlanta Braves were the first Major League team in the south.

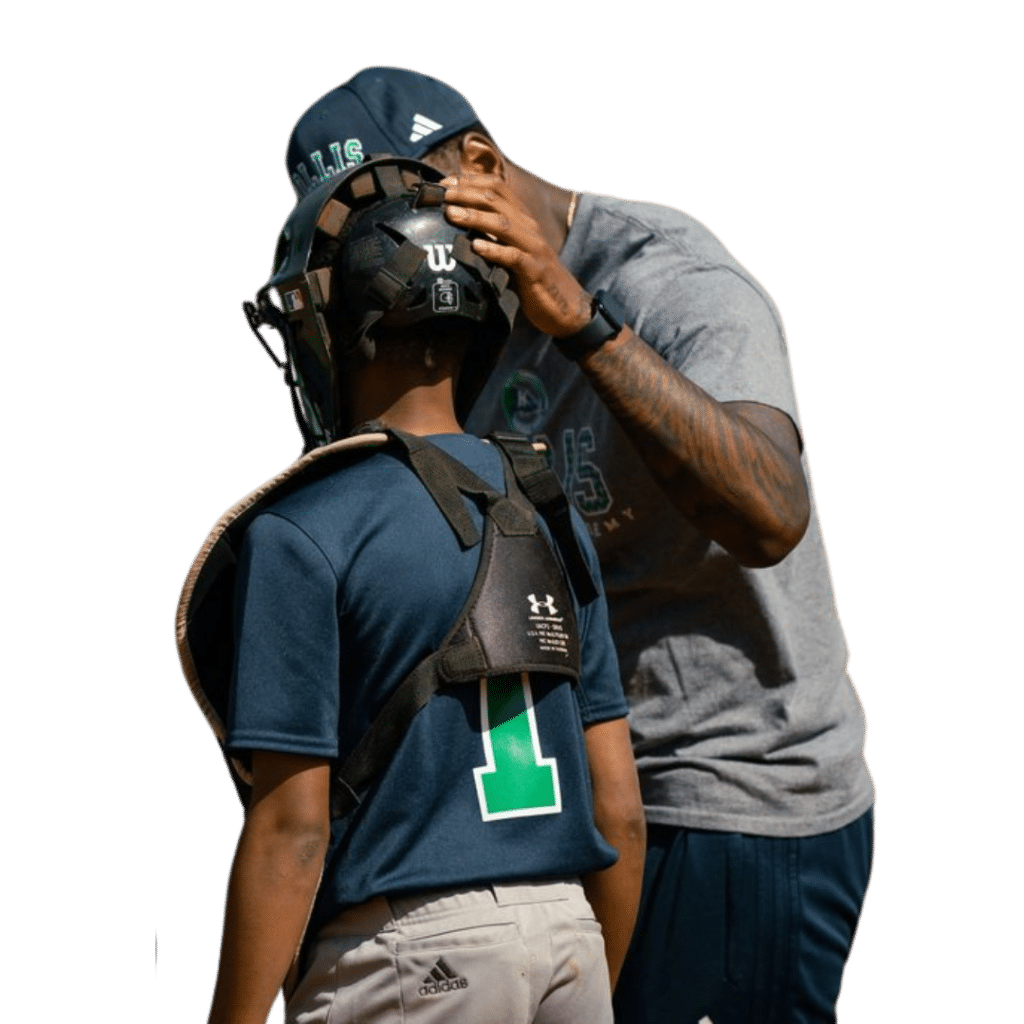

Today, when I look out across our city, I see progress. Some of the progress can be traced back to sports. As the co-founder of L.E.A.D., I am able to use sports as a vehicle to help Black males in Atlanta’s inner city overcome crime, poverty and racism.

|

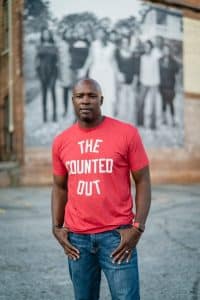

| Photo of C.J. Stewart by Steve West |

As I continue to help build the minds and stature for some of Atlanta’s inner city Black youth, I cannot help sit back and reflect on how the road has led me to this place, at this time. As a husband and father, I am blessed to have had a hand in raising our children to always reach for the highest star.

My oldest daughter, Mackenzi, graduated from The Westminster School in 2019 with honors, while being a three-time state champion in tennis. Mackenna, my youngest daughter, is a 7th grader at The Lovett School. She is working to become a professional tennis player by age 15.

Both The Westminster School and The Lovett School are nationally respected institutions for sports and academics. Those are two of the reasons my daughters are a part of these K-12 institutions. The networking opportunities is the other. Mackenzi is a freshman student-athlete (tennis) at Howard University who is majoring in Afro-American History. She wants to be an education reformist who can educate and inform the masses about key concepts, events, people, etc., that were conveniently and intentionally left out of our history books. Mackenna wants to be a social activist.

At these schools, participating in sports and/or the arts is expected of everyone, regardless of their skill level. Being just a student today just is not going to happen.

The common thread of opportunity, as you can see, is that sports gives everyone a path toward intellectual, social and emotional growth. These are the very principles our L.E.A.D. Ambassadors embrace. The opportunity to step on to a playing field can be transformational. In sports, we find the balance between mind, body and spirit. It is just that this transformational experience must be something everyone—in all walks of life— should have the chance to develop.