Read the full story from Shoutout Atlanta

L.E.A.D., Inc. | L.E.A.D. Center For Youth

- 680 Murphy Avenue Suite #4128 Atlanta GA, 30310

- info@leadcenterforyouth.org

by gmg

Read the full story from Shoutout Atlanta

by C.J. Stewart

A Coach is someone who moves others. In fact, before the word coach was used in the context of sports, it was reserved strictly for transportation. A coach moved you to where you were supposed to be. Today, oftentimes because of the fear of accountability, not so much.

A Coach is someone who moves others. In fact, before the word coach was used in the context of sports, it was reserved strictly for transportation. A coach moved you to where you were supposed to be. Today, oftentimes because of the fear of accountability, not so much.

This morning, I found out that Coach Mike Hurst passed after a long battle with cancer. Coach Hurst was a white man and I am a Black man. To some, race doesn’t matter, but to me, it did when I met him at age 16. He was recruiting me to play baseball for him at Georgia State University (GSU). At the time, I was living in the Bankhead community in the inner-city of Atlanta and was one of the best players in the state.

I love Atlanta, and at that time in my life, I couldn’t see myself leaving the city to attend college. I was also very immature. In a lot of ways, I needed the support of family and the familiarity of my city.

I was being recruited by several predominantly white institutions (PWIs) across the country and all of the top historically black colleges and universities (HBCU)s. Ultimately, I chose GSU because of Coach Hurst—a move that upset a lot of HBCU coaches.

When I reflect on why I chose Coach Hurst, the answer is in his last name:

Help is what you offer people when they are weak. As a teenager, I lacked the social-emotional learning capacities that I teach young men today. I wasn’t as strong as I needed to be in the areas of self-identity, social connections and social skills. Subsequently, and to the disappointment of Coach Hurst, I failed out of GSU at the end of my freshman year. Yet he still continued to help me—even through adulthood.

Prior to Coach Hurst, as an African-American young man, I had only a couple of meaningful relationships with White men. The vast majority of the people I knew were Black. Most of what I knew about White people, I learned from watching television. And a lot of that was negative. Coach Hurst helped me to see that race relations is not the problem—white supremacy is.

Coach Hurst was uncompromising on values like being punctual, prepared, making promises and keeping promises. Being a college student-athlete was hard for me. I learned a lot from my failures, and as an adult, he constantly reminded me that even though I didn’t get my degree from GSU, I was not a failure. Today, I am a “consequential, uncompromising on values” type of coach just like he was.

Respect is earned. The respect that Coach Hurst showed me when I became a coach was truly meaningful. Since the first day we met, he became my friend, confidant and advocate.

Coach Hurst was a great coach because he was a servant first. He made so many sacrifices with his time, energy and expertise. His beautiful wife, Carol, can attest to the late nights coming home from games and practices. He probably mentioned my name several times in some late-night rants trying to figure out how to motivate me to meet expectations in the classroom and on the field.

GSU didn’t have a large financial budget, but we had a really nice field, located several miles away from campus in Decatur, Georgia. He cut the grass and painted dugouts. You name it; he did it. He also brought good people together to become members of the GSU Panthers family.

Values are what you believe and virtues are what you do. Coach Hurst was a servant.

Coach Hurst was tough to play for. He knew what you were capable of doing and he designed practices for you to become your best. Then he’d put you on the field to do your best. When I didn’t do my best, he was relentlessly tough on me. If I did something wrong in private, we dealt with it in private. But if I did it in public, rest assured he would deal with it publicly. Toughness develops character.

To Ms. Carol, may God continue to bless you. You are an amazing woman. You were there for Coach until he took his final breath. I am inspired by your love and commitment to him.

To my fellow GSU teammates, GSU alumni and current GSU student-athletes, let’s continue daily to become the best versions of ourselves. Our struggles will lead to success, so let us use our success to serve others. That’s what significance is all about—using our success to serve others.

My friend and fellow GSU alum Rusty Bennett told me this morning about a conversation he had with Coach Hurst last year. Coach told him he wasn’t afraid of dying. He was dealing the most with the fact that he would miss all of us. We miss you too, Coach.

Rest in peace, my friend, my advocate, my Coach.

by C.J. Stewart

Black History Month

If Black History Month is a call to America to see us, then Black Lives Matter is a scream. We saw that more clearly last year than we have in quite awhile. Black people are sick and tired of being terrorized and oppressed. Yes, there are well-to-do Black people in America, but their fame and fortune are not enough for Black folks by the masses to get the benefit of the doubt, respect and trust they deserve from their fellow White counterparts..

Black History Month has become known as the time when Black people matter the most to America. A time when it’s ok to talk about the experiences of Black people; well some of them anyway. This year, I’m proposing an interesting thought: “How would America respond to a Black History Year?”

After all, the Black History celebration started out as one week, not a full month. Maybe we got a shot at a full year.

Judging from the recent presidential election, America remains a divided country across many lines. Gun rights. Abortion. Military spending. Immigration. Drug legalization. School choice. For each of these, Republicans and Democrats hold different views.

That’s why I suspect there would be a similar divide regarding proposing a Black History Year. I could hear the sentiment now, “Black people need to be satisfied with what they have.”

For too long, Blacks have been America’s most oppressed people, also doubling as a scapegoat whenever White America is challenged to take responsibility for its role in this oppression. Rising from our government sponsored subjugation to an equal footing with White people may seem a bit threatening for some, especially if people thought we’d treat White people as poorly as some have treated us.

Throughout history, Black people have been peaceful and loyal —even when any reasonable person would understand if we weren’t. Black people have always given White people the benefit of the doubt, treated them with respect and put their trust in them to do what’s right.

Those criteria—getting the benefit of the doubt, being treated with respect and earning trust—are the things Black people want and deserve in return.

I am an extrovert. I love people. To me, love is as much a feeling as it is a decision. I want the best for people. I even want hateful people to reach the point where they can experience the kind of peace that only comes, in my opinion, from having a relationship with God the Father.

Everybody is important, but I don’t believe anyone has the capacity to care about everybody. To care about everybody is to prioritize them—to respect their well-being. I can pray for everyone, but I cannot care for them.

Asking people this question is a way for me to share what I care about with them. This is a Should Ask Question” (SAQ) rather than a Frequently Asked Question (FAQ). SAQs entice people to go deeper into their thought process. SAQs are a gift. They make you wrestle with your thoughts. After all, our thoughts become our actions, so we must make sure we’re thinking the right way in order to do the right things.

America is still a racialized country. Racism is about power before it is about people. It becomes about people when we are categorized by race. A race has a winner and a loser. Black people have been losing since America was created. We will never be able to be equal until we matter. It is one thing to say, Black Lives Matter, but it is something else to do something crazy to prove it.

In the 1960s, political and business leaders in Atlanta created the slogan “A City Too Busy to Hate.” They adopted the slogan as a way to prove they were more progressive than neighboring cities like Birmingham, Memphis, Charlotte and Jacksonville.

How did they prove it? One way was to bring the Braves from Milwaukee to Atlanta. This created the first Major League sports team in the Jim Crow South and, most importantly, the first African-American to play professional sports in the Jim Crow South. Prior to the Braves coming to Atlanta, Major League sports teams couldn’t compete in the South. When the Braves came here with Hank Aaron as the franchise player, Atlanta proved it was a “City Too Busy to Hate.” Soon, major corporations like Delta and Coca Cola followed suit.

Fast-forward to today and America as a whole has yet to prove it is too busy to hate. That’s why our collective reflection during Black History Month is so important. Black History month is just as important as celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ during Christmas. Because there is so much ignorance about the importance of Black history, we still have much to learn.

People need to know there is no American history without Black history. Black people were stolen from their homes, brought here and enslaved to build this country and provide White people with a life of leisure and wealth building. In light of the foundational, meaningful contributions we’ve made to America, under terror and duress no doubt, it’s unfathomable that we are still on the losing end of its race relations. America must be empathetic about the negative plight of Black people, but that won’t happen unless people know what the plight has truly been. Showing empathy is what we do with someone. Empathy is about struggling with someone. In contrast, sympathy is feeling sorry for someone.

Where we are. Who we are?

My first memory of Black History Month was attending Grove Park Elementary School in Bankhead, an inner city neighborhood in Atlanta. During those early years, I learned about Harriet Tubman, Fredrick Douglas and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a fellow Atlanta Public Schools (APS) alumni.

I have always felt that too many people put the burden of the success of the Civil Rights Movement all on Dr. King’s shoulders. That’s unfair to him and disrespectful to the many courageous Black people who contributed to The Movement during that time and leading up to it. I would have loved to learn more about other APS alumni like Vernon Jordan, Don Clendenon, Herman Russell, Walt Frazier and Gladys Knight. It would have been good to learn the history of Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, Assata Shakur, Fred Hampton, Angela Davis and Malcom X. With methods that were different from Dr. King’s, they were seen as radicals, even though they were effective in their own right.

A personal story that I hope helps bring my story to life, when my youngest daughter, Mackenna, was 10 years old, she wanted to teach her 5th grade classmates about Juneteenth. It is important to note that Mackenna went to Trinity School, a private school in Buckhead where the vast majority of her classmates were White and had never heard of Juneteenth. Admittedly, I had only heard of it myself a few months prior, but Mackenna had studied it and presented it with such passion and compassion. The joy that was all over her spirit as she shared truths about Juneteenth while her and her classmates ate red hot sausage links, black-eyed peas and cornbread was joy born out of pride for her ancestors and her heritage. Seeing her do this inspired me to learn more about Black History and present it with passion and compassion.

I hope this year’s Black History Month continues to see improvements like that. I hope that Americans feel convicted to act upon what they are learning rather than feel guilty. Guilt is paralyzing, while conviction is empowering.

I want non-Black people to accept the calling and bear the responsibility to be anti-racist. Racism is as real as the air we breathe. As we sit today, White people are winning the race in America, not because they are better, but because we have a system that is perfectly and precisely designed for them to win.

America will never be great if Black people in vast numbers are not doing great.

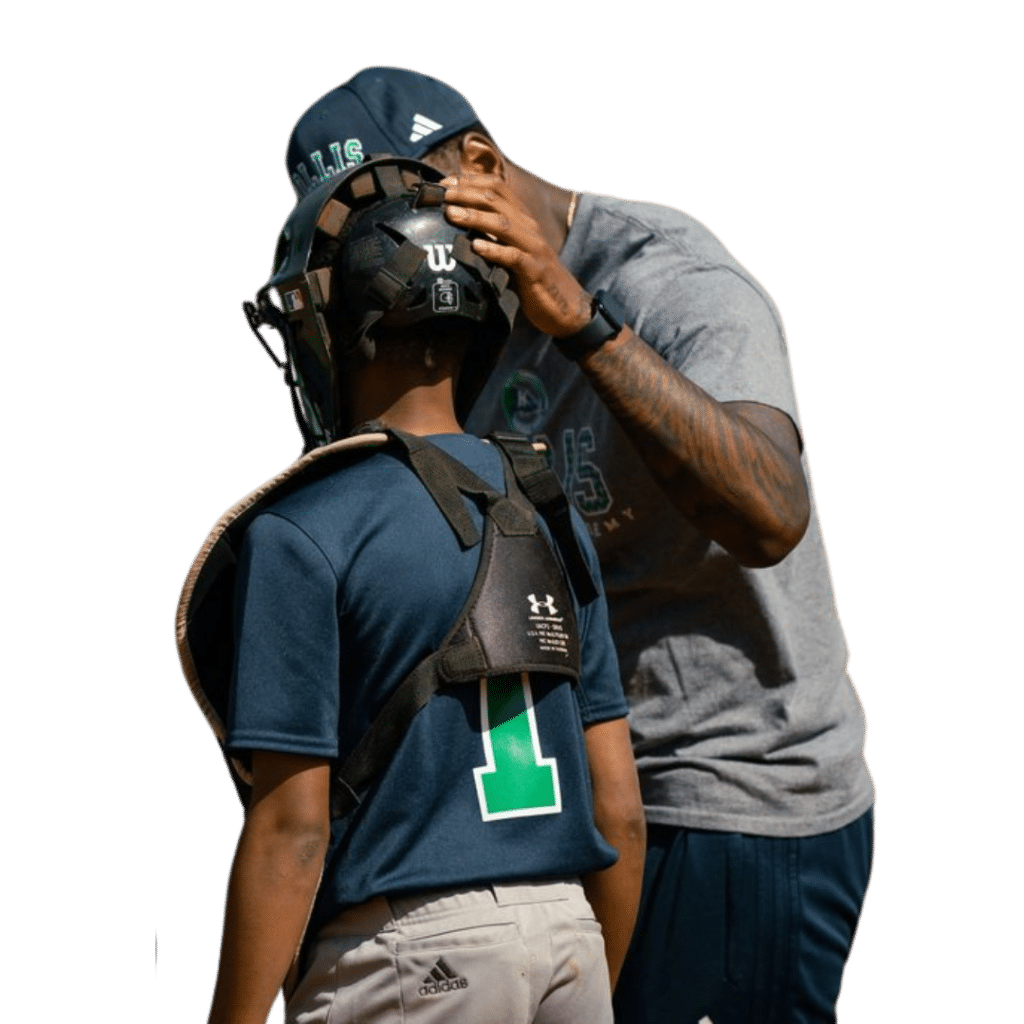

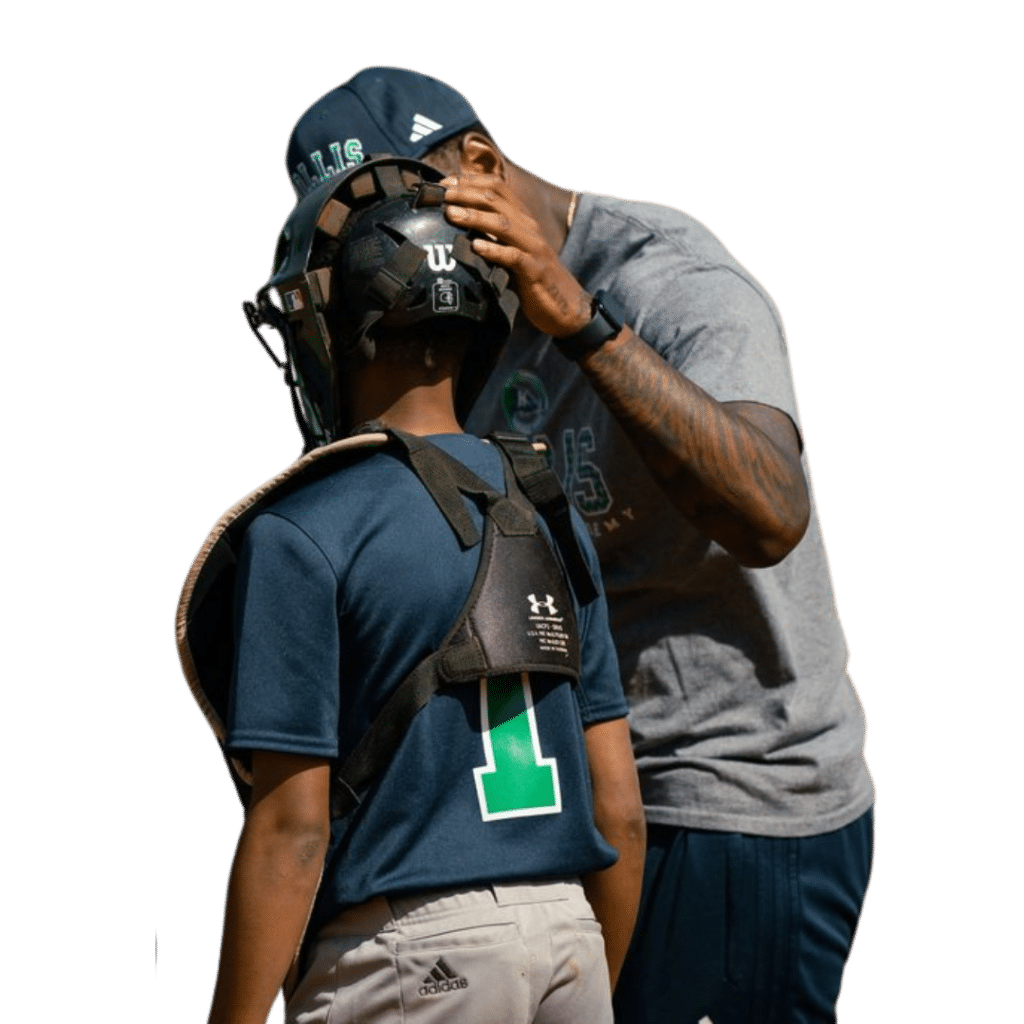

That’s why learning about Black History is a year-round experience at L.E.A.D. It has to be in order for us to fulfill our organization’s mission and vision. L.E.A.D. stands for Launch, Expose, Advise, Direct. Our mission is to empower an at-risk generation to lead and transform their city of Atlanta by using the sport of baseball to teach Black boys how to overcome three curveballs that threaten their success: crime, poverty and racism. Our vision is to develop Black boys into Ambassadors who will lead their City of Atlanta to lead the world.

To learn more about Black History Month, click here

Photo credits to Jay Boatright

One of the Black History Week and Month founders,

Carter G. Woodson

by C.J. Stewart

This article was originally published in Atlanta Magazine.

Growing up in Atlanta as a young baseball player, I naturally idolized Hank Aaron. But over the years, I have identified with his journey and been inspired by his character in ways far deeper than simple admiration for a remarkable athlete.

Hank Aaron grew up in a loving home in Mobile, Alabama. His family—like most of our families in L.E.A.D. and like my own family—was poor, and they faced the social-economic struggles that always come with poverty, as well as the challenges of Jim Crow racism. I know from experience that for Black Americans, education has always been viewed as a powerful tool not only for edification, but also for assimilation. Throughout my life, I’ve heard elders and ancestors express, If we can just show white people that we are as smart as they are, it will open doors. Understanding the weight that education holds in the Black community, I can imagine how difficult it must have been for Mr. Aaron to leave school for professional baseball. I faced the same decision when I decided to pursue the Chicago Cubs over going to college. I know Mr. Aaron must have met with a lot of opposition because of his decision, and I thank God that whatever was convicting his heart to follow his dream had his mind so stayed on it that he didn’t allow himself to be deterred.

Now, I know Moses Fleetwood Walker and Jackie Robinson blazed significant trails for Blacks in baseball, but what makes me identify so closely with Mr. Aaron is the impact of his presence in the Jim Crow South. The Braves organization, with its star slugger, moved to Atlanta from Milwaukee just two years after the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964. They were the first major league professional sports team in the South, and Mr. Aaron’s very presence helped give leaders here the audacity and permission to call Atlanta “The City Too Busy To Hate.”

Only Atlanta was not too busy to hate. As Mr. Aaron closed in on Babe Ruth’s homerun record, he faced unprecedented harassment and danger. On the road, he couldn’t stay with the rest of the team, and he faced a barrage of death threats. I can’t imagine the anxiety of stepping on the field not knowing if anyone was going to harm you while you were playing.

Uncertainty haunted Black Americans during this time, making many wonder constantly, Did I do anything to piss off a racist white person enough for them to visit my home? I can imagine there were many sleepless nights in the Aaron household. One thing most people know about me is that I love my wife and daughters with a fierce, protective love. I cannot imagine leaving home, knowing that my family faced FBI-level threats, and still going to work and hitting bombs daily. I always say that talent is what you do well, but skills are what you do well even when you’re under stress.

Mr. Aaron’s story speaks volumes to me. My life parallels his in a lot of ways, and I will continue to follow his example and use the platform that baseball has given me to raise up poor, Black boys in this city who can walk in my shoes and, maybe, even Mr. Aaron’s.

by gmg

© Copyright L.E.A.D. 2024 All Rights Reserved. Powered By Diamond Directors Inc.