Black History Month

If Black History Month is a call to America to see us, then Black Lives Matter is a scream. We saw that more clearly last year than we have in quite awhile. Black people are sick and tired of being terrorized and oppressed. Yes, there are well-to-do Black people in America, but their fame and fortune are not enough for Black folks by the masses to get the benefit of the doubt, respect and trust they deserve from their fellow White counterparts..

Black History Month has become known as the time when Black people matter the most to America. A time when it’s ok to talk about the experiences of Black people; well some of them anyway. This year, I’m proposing an interesting thought: “How would America respond to a Black History Year?”

After all, the Black History celebration started out as one week, not a full month. Maybe we got a shot at a full year.

Judging from the recent presidential election, America remains a divided country across many lines. Gun rights. Abortion. Military spending. Immigration. Drug legalization. School choice. For each of these, Republicans and Democrats hold different views.

That’s why I suspect there would be a similar divide regarding proposing a Black History Year. I could hear the sentiment now, “Black people need to be satisfied with what they have.”

For too long, Blacks have been America’s most oppressed people, also doubling as a scapegoat whenever White America is challenged to take responsibility for its role in this oppression. Rising from our government sponsored subjugation to an equal footing with White people may seem a bit threatening for some, especially if people thought we’d treat White people as poorly as some have treated us.

Throughout history, Black people have been peaceful and loyal —even when any reasonable person would understand if we weren’t. Black people have always given White people the benefit of the doubt, treated them with respect and put their trust in them to do what’s right.

Those criteria—getting the benefit of the doubt, being treated with respect and earning trust—are the things Black people want and deserve in return.

I am an extrovert. I love people. To me, love is as much a feeling as it is a decision. I want the best for people. I even want hateful people to reach the point where they can experience the kind of peace that only comes, in my opinion, from having a relationship with God the Father.

Everybody is important, but I don’t believe anyone has the capacity to care about everybody. To care about everybody is to prioritize them—to respect their well-being. I can pray for everyone, but I cannot care for them.

Asking people this question is a way for me to share what I care about with them. This is a Should Ask Question” (SAQ) rather than a Frequently Asked Question (FAQ). SAQs entice people to go deeper into their thought process. SAQs are a gift. They make you wrestle with your thoughts. After all, our thoughts become our actions, so we must make sure we’re thinking the right way in order to do the right things.

America is still a racialized country. Racism is about power before it is about people. It becomes about people when we are categorized by race. A race has a winner and a loser. Black people have been losing since America was created. We will never be able to be equal until we matter. It is one thing to say, Black Lives Matter, but it is something else to do something crazy to prove it.

In the 1960s, political and business leaders in Atlanta created the slogan “A City Too Busy to Hate.” They adopted the slogan as a way to prove they were more progressive than neighboring cities like Birmingham, Memphis, Charlotte and Jacksonville.

How did they prove it? One way was to bring the Braves from Milwaukee to Atlanta. This created the first Major League sports team in the Jim Crow South and, most importantly, the first African-American to play professional sports in the Jim Crow South. Prior to the Braves coming to Atlanta, Major League sports teams couldn’t compete in the South. When the Braves came here with Hank Aaron as the franchise player, Atlanta proved it was a “City Too Busy to Hate.” Soon, major corporations like Delta and Coca Cola followed suit.

Fast-forward to today and America as a whole has yet to prove it is too busy to hate. That’s why our collective reflection during Black History Month is so important. Black History month is just as important as celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ during Christmas. Because there is so much ignorance about the importance of Black history, we still have much to learn.

People need to know there is no American history without Black history. Black people were stolen from their homes, brought here and enslaved to build this country and provide White people with a life of leisure and wealth building. In light of the foundational, meaningful contributions we’ve made to America, under terror and duress no doubt, it’s unfathomable that we are still on the losing end of its race relations. America must be empathetic about the negative plight of Black people, but that won’t happen unless people know what the plight has truly been. Showing empathy is what we do with someone. Empathy is about struggling with someone. In contrast, sympathy is feeling sorry for someone.

Where we are. Who we are?

My first memory of Black History Month was attending Grove Park Elementary School in Bankhead, an inner city neighborhood in Atlanta. During those early years, I learned about Harriet Tubman, Fredrick Douglas and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a fellow Atlanta Public Schools (APS) alumni.

I have always felt that too many people put the burden of the success of the Civil Rights Movement all on Dr. King’s shoulders. That’s unfair to him and disrespectful to the many courageous Black people who contributed to The Movement during that time and leading up to it. I would have loved to learn more about other APS alumni like Vernon Jordan, Don Clendenon, Herman Russell, Walt Frazier and Gladys Knight. It would have been good to learn the history of Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, Assata Shakur, Fred Hampton, Angela Davis and Malcom X. With methods that were different from Dr. King’s, they were seen as radicals, even though they were effective in their own right.

A personal story that I hope helps bring my story to life, when my youngest daughter, Mackenna, was 10 years old, she wanted to teach her 5th grade classmates about Juneteenth. It is important to note that Mackenna went to Trinity School, a private school in Buckhead where the vast majority of her classmates were White and had never heard of Juneteenth. Admittedly, I had only heard of it myself a few months prior, but Mackenna had studied it and presented it with such passion and compassion. The joy that was all over her spirit as she shared truths about Juneteenth while her and her classmates ate red hot sausage links, black-eyed peas and cornbread was joy born out of pride for her ancestors and her heritage. Seeing her do this inspired me to learn more about Black History and present it with passion and compassion.

I hope this year’s Black History Month continues to see improvements like that. I hope that Americans feel convicted to act upon what they are learning rather than feel guilty. Guilt is paralyzing, while conviction is empowering.

I want non-Black people to accept the calling and bear the responsibility to be anti-racist. Racism is as real as the air we breathe. As we sit today, White people are winning the race in America, not because they are better, but because we have a system that is perfectly and precisely designed for them to win.

America will never be great if Black people in vast numbers are not doing great.

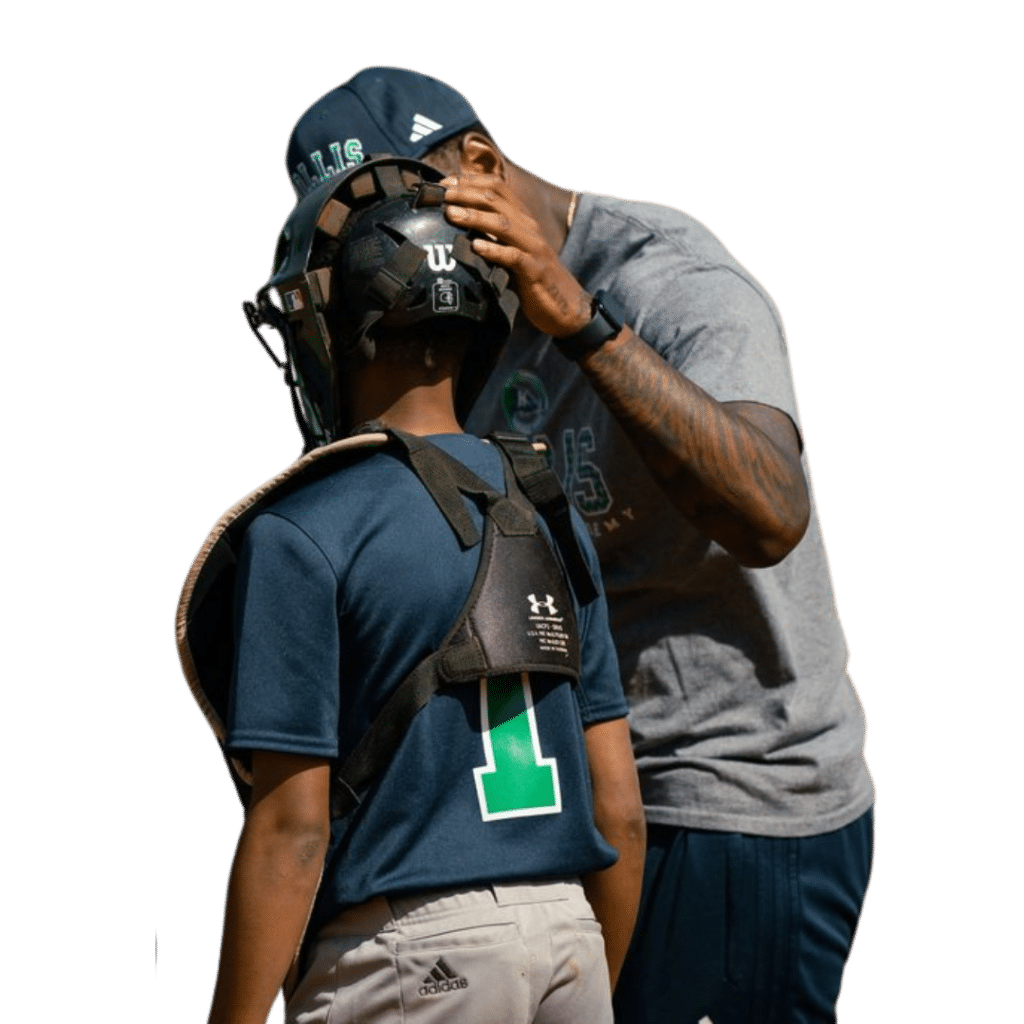

That’s why learning about Black History is a year-round experience at L.E.A.D. It has to be in order for us to fulfill our organization’s mission and vision. L.E.A.D. stands for Launch, Expose, Advise, Direct. Our mission is to empower an at-risk generation to lead and transform their city of Atlanta by using the sport of baseball to teach Black boys how to overcome three curveballs that threaten their success: crime, poverty and racism. Our vision is to develop Black boys into Ambassadors who will lead their City of Atlanta to lead the world.

To learn more about Black History Month, click here

Photo credits to Jay Boatright

One of the Black History Week and Month founders,

Carter G. Woodson