(This blog was written after an experience I had on one day prior to the 2020 Presidential Election.)

I make it my business to sit in places where I’m not expected to be or “supposed” to be. One such place is bible study groups made up of predominantly White men. I am a follower of Christ. I was raised that way. In my adult life, I got the blessed opportunity to unknow the Christ that White Supremacy built, and connect with the true Christ of the Scriptures. The Christ from Genesis to Revelations; a privilege that my early ancestors didn’t have as their enslavers didn’t want them reading about nobody’s Exodus.

I’ve had a lot of emotions and reflections during this current presidential campaign. During a conversation with my wife, we started talking about the differences between appreciation and allegiance.

Appreciation is the recognition and enjoyment of the good qualities of someone or something.

Allegiance is loyalty or commitment to a group or cause.

As a Black man having citizenship in a country that’s been trying to kill and disenfranchise Black people since the days our ancestors were stolen from Africa and enslaved on this soil, it should be relatively clear why pledging allegiance to my country is difficult for me. I’m not going to burden myself with an exhaustive history lesson on the disenfranchisement of enslaved Africans and their descendants in America; there are far too many resources out there that already do this in a more systematic and thorough way than I ever could. I recommend the following: Equal Justice Initiative, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture & We Are Push Black.

Getting back to these spaces…

I’m a part of a bible study that’s made up of White men. From what I can tell from the Zoom calls I’ve been on, I’m the only Black man. During the opening prayer this morning, a gentleman that I respect prayed the following in part (and I paraphrase), “…God please bless and strengthen Donald Trump as he seeks to lead this nation from Muslim rule and saves the unborn from abortion…”

I was stunned. Now praying for leaders isn’t something that’s foreign to me. I feel the Bible tells us to do this and I attend Elizabeth Baptist Church under the leadership of Dr. Craig L. Oliver, Sr. where we always pray for our leaders. In my household and in my church family, however, we pray a little differently for our leaders. We pray that God’s will be done relative to their leadership. We pray that our leaders will yield their hearts and minds to the will of God. After all, the Word of God does tell us that he sets up kings/kingdoms and he takes them down as well.

The prayer I heard this morning was one of trying to get God to bend to the will of the man who was praying and the cause he represents. As a follower of Christ, I have lots of experience with trying to make God do what I want Him to do – it never works. It never works, that is, if I’m not in alignment with Him. As I listened to the verbal affirmations from the other White men on the call, I wondered to myself, did they stop to think about their Black brother in Christ on the phone and how what was being said would affect me? Did it even occur to them that I may feel that Donald Trump and everything he stands for is a threat to me and everyone who looks like me? Obviously not, because after everyone (except me) uttered a collective ‘Amen’ they moved to the first item on the agenda like everything was cool.

After their amens, I immediately hung up. I didn’t hang up at the moment I was offended because I wanted to stay on to listen to all that would be said in his prayer. I try my best to live by the philosophy that I learned from one of Dr. Covey’s books – seek first to understand, then to be understood. I must admit, I’m still at a loss here. I don’t understand how so many White people can’t see the threat that Donald Trump poses to Black people and basically anyone who isn’t White, male, and straight. I don’t understand why the White men on that call this morning didn’t think about my feelings relative to that prayer.

I’m not sure whether I’ll log into that Bible study group again. I’m trying to figure out if I have enough self-control and sanity to subject myself to that hostile space; trying to figure out if my being present to learn and to teach others is worth me losing my cool or my mind. Pray for me on that one.

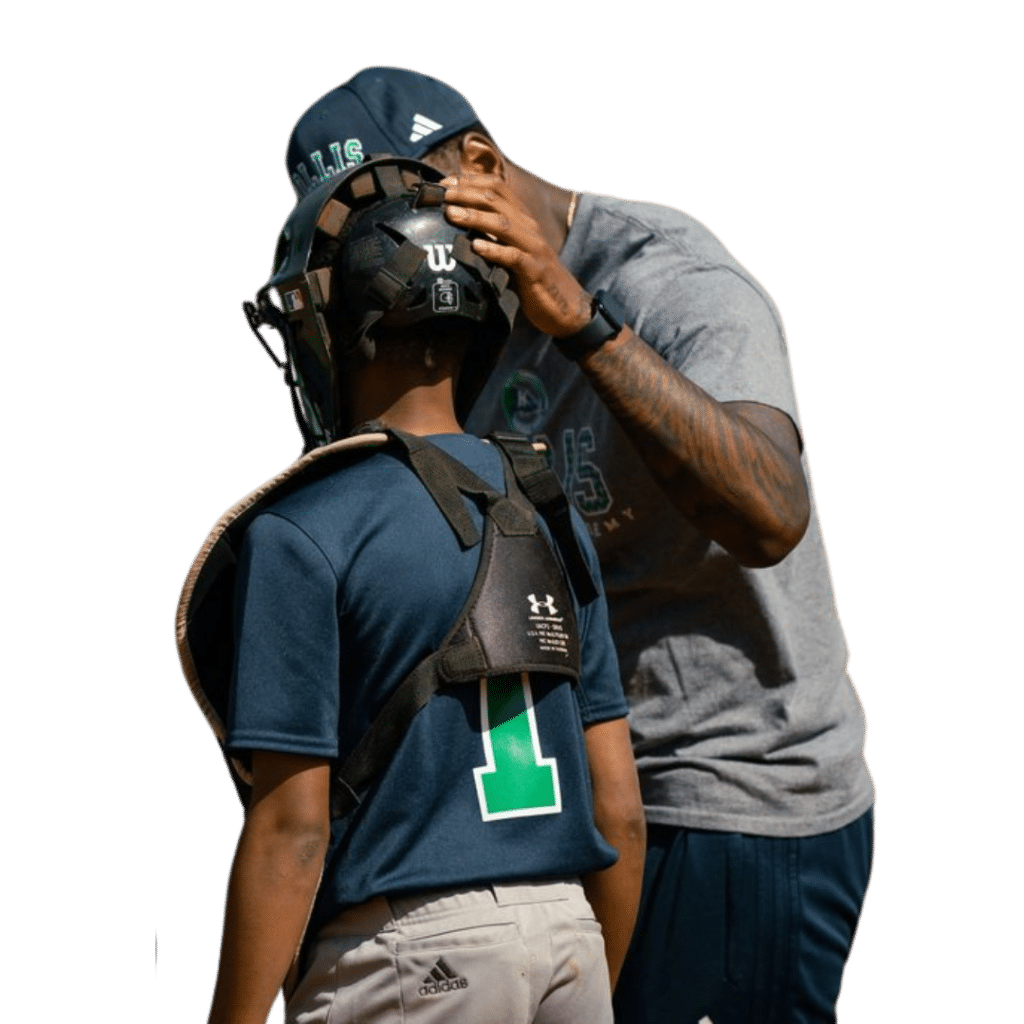

What I will continue to do is lead and protect my family and the Black boys I serve in L.E.A.D. I will continue to enlighten, correct, and educate my White friends on the Black experience and what I expect them to do to make it what it should be in America.

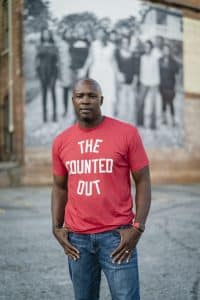

I will also continue to be an unapologetic Black man. That’s who God made me and that’s who I’m committed to being wherever He has me showing up.

(Photo by Steve West)