Baseball is called America’s pastime. I have always wanted to believe that. I have spent my life chasing the dream and helping others do the same. When I look at the game today, I see it as a microcosm of the American Dream. Some people get what is needed to follow their path and enjoy the experience, while others do not.

If you look closely at the decline of African-American participation in the sport, you will see what I see. The decline is a social justice issue that cannot be solved until we view it through that lens.

The issue is something that is near and dear to my heart. When I challenge white college coaches about not having as many African-American players as others on their rosters, many say their edict is to recruit the best players in order to win.

This opportunity was made possible after Jackie Robinson carved a path for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech. The trials and tribulations he endured proves, even today, that they must be adhered to with seriousness.

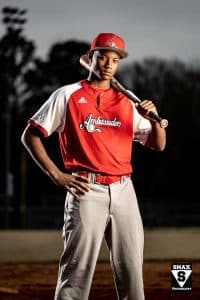

So yes, we need more Black boys to participate in baseball. To do so, we must first own up to the fact there are tens of thousands eagerly awaiting for their opportunity.

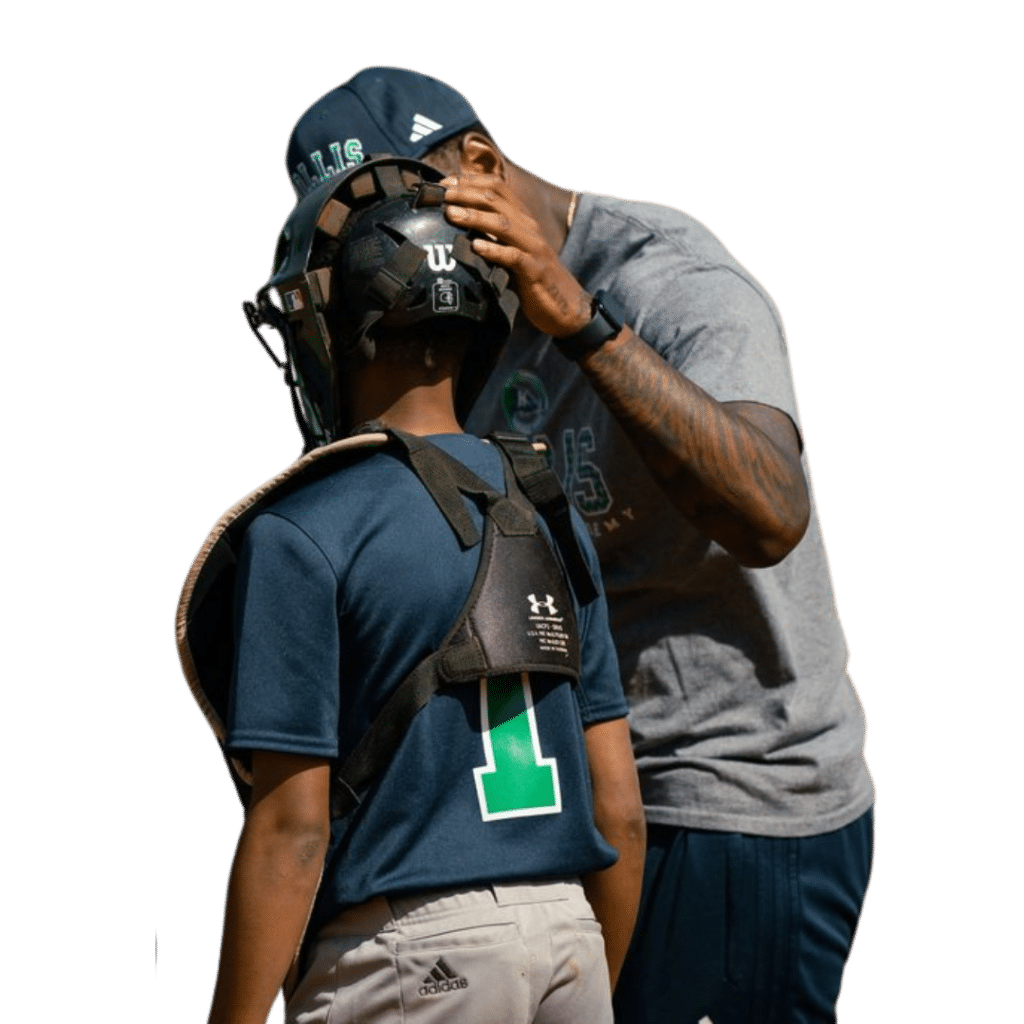

|

| C.J. Stewart with youth in the Northwest Atlanta neighborhood that he grew up in. Photo by Eriel Dunnam. |

Rhetoric suggests that African-American males are “born good athletes,” yet some believe they are not capable of throwing, catching or hitting a baseball like the Negro Legends that helped save Major League Baseball.

Do you believe that?

Let us say that only 10 percent of those 4,900 African-American high schoolers playing baseball were “good enough” to compete in the classroom and on the baseball field at the NCAA D-I level.

That number is 490.

That means that at any given time, there should be close to 490 African-American males playing baseball at the NCAA D-I level. Why is it not a reality? I believe there are three threats impeding their progress:

1. Implicit bias

2. Colorblindness

3. Blackballing

To help turn this way of thinking around, I am proposing a five-point plan that every baseball organization and community can implement. Let us call it the 5 P’s:

1. Participate

There is no shortage of opportunities for African-American youth to participate in baseball because it is the easiest thing to organize. Participation is the first step to increase the amount of players performing at the collegiate and Major League levels.

2. Practice

Once a player demonstrates a love for the game at the participatory level, it is time to learn how to practice. Thisrequires commitment and discipline. Commitment is a promise made and kept. Discipline is doing the things that need to be done even when you do not want to do them.

Having a love for the game is important because you cannot master something without loving it. Players who love baseball possess commitment and discipline. If stressed properly, both of these characteristics should last a lifetime, helping a player win on and off the field. Commitment and discipline are skills that last a lifetime.

3. Play

Learning how to play baseball does not make sense if you do not know how to practice. Playing the game is nothing short of testing what you are working on at practice. Translation: Practice prepares you to play in the game, and the game dictates what you work on in practice.

Growing up, I did not have access to coaches who were former MLB players. Most of my coaches loved the game and a few played at the D-II level. I learned how to play under their leadership because they allowed me to play the game. We focused on the mistakes made at practice and learned how to make adjustments.

I remember playing in my neighborhood with a tennis ball, a stick and some friends. We received lots of reps uninterrupted by a “coach.” We were our own coaches. As we see too often, coaches can unintentionally coach the critical thinking skills out of a player.

4. Perform

When a player reaches the level that allows him to perform, he has earned the right to compete at the collegiate and/or professional level. Performance requires skills developed as a result of practicing under pressure. The skill yields game impact. Strike the right balance and you can avoid excuses like: “I’m tired.” “I’ve never faced this type of pitcher.” “I’m hurt.”

Performance is the ability to get things done in spite of the circumstances. Players who perform know their ability so well that they can make guarantees and execute. They do not focus on getting hits; they focus on executing what it takes to get a hit (timing and tracking pitches, repeating their approach, etc.). Getting hits is the effect, not the cause.

Players cannot learn how to perform until they learn how to participate, practice and play.

5. Protection

The other P’s do not mean anything if we are not protected. When African-American males do not feel their dreams are being protected, they oftentimes are unable to reach an optimum level of performance. Nobody wants to feel like they are doing something in vain.

African-American males often go unprotected because they are silent and deemed naturally resilient. Their silence could be the result of a lack of self-confidence. Their resilience could be the result of having to make things happen on their own.

Boys should not have to figure things out of their own. African-American males need heroes more than they need coaches.

As we see too often, structural racism is a real thing. It shows up in baseball as implicit bias, colorblindness and blackballing. It is time to break the chain.