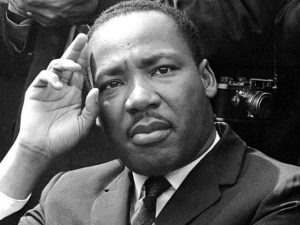

Eighty four years ago on a Tuesday afternoon, a reverend and his wife welcomed the birth of their second child — a son — at their family home at 501 Auburn Avenue N.E. in Atlanta, GA. That child would grow up to become one of the greatest leaders in world history, a man who promoted social change facilitated by education, community involvement and non-violence. That man was Martin Luther King, Jr.

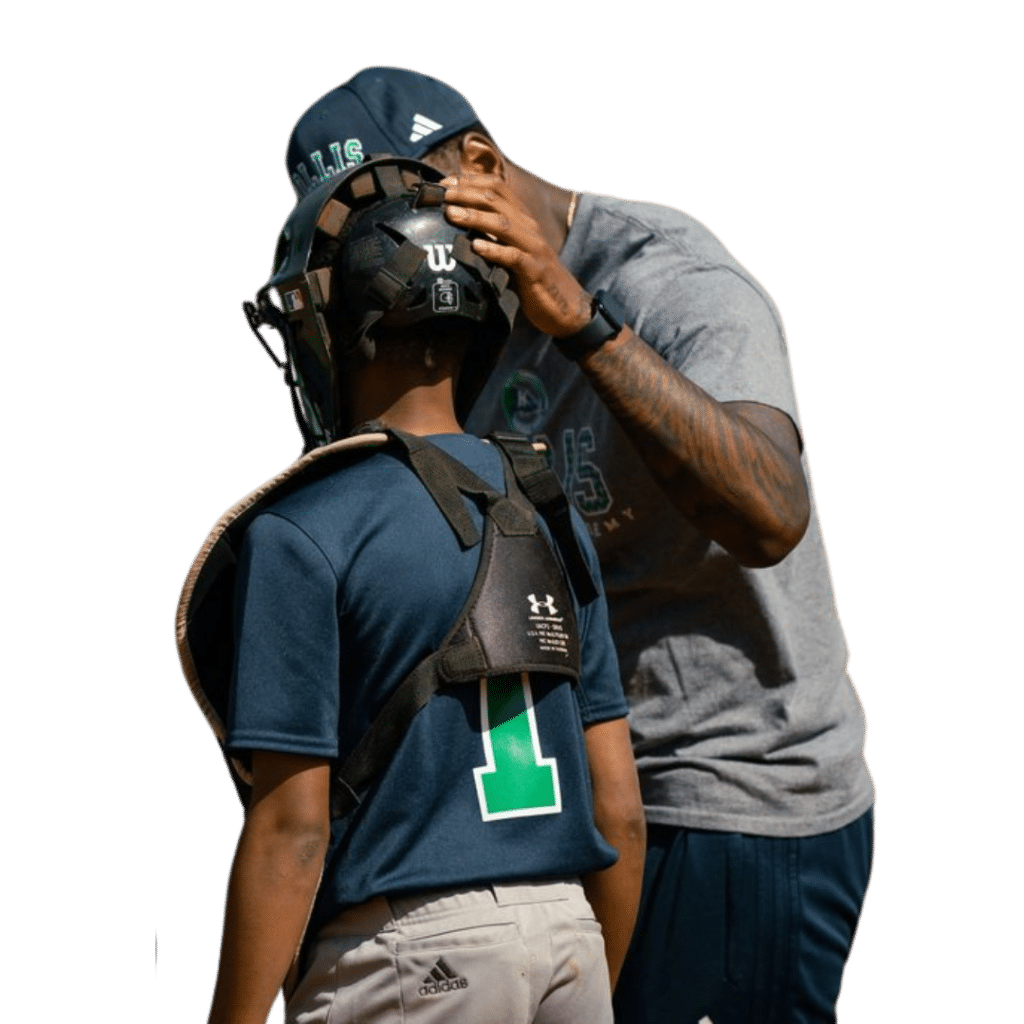

Eight years and one week after King gave his final speech, where he proclaimed that he had “been to the mountaintop,” and told African-Americans that they would get to the “Promised Land,” C.J. Stewart was born in the Hollywood Courts project of Atlanta. As a child, Stewart excelled both academically and athletically. He graduated with honors from Westlake Magnet High School and was drafted by the Chicago Cubs organization. After his playing career ended, Stewart opened his own baseball hitting instruction company. Through his company, Diamond Directors Consulting, he has worked with MLB’s rising stars, including, Jason Heyward, Andruw Jones and Andrew McCutchen.

Stewart turned his baseball talent into a successful career. Yet, he is aware that if it weren’t for the assistance of others, he would have never achieved such success. Growing up in the projects, Stewart’s family’s finances only allowed the budding baseball talent to play at the high school level. For Stewart, there was no extra money lying around for the batting coaches, physical training sessions or participation in competitive teams necessary to make it to the major leagues. Luckily for him, an Atlanta police officer with a passion for baseball entered his life. T.J. Wilson’s love for baseball drove him to spend many days at Westlake High School’s baseball field. Aware of the young Stewart’s talent, Wilson took Stewart under his wing. He would pick Stewart up from school, make sure that he completed his homework and take him to and from a training facility 45 minutes away three days a week. Without the assistance, care and concern that Wilson showed Stewart, it’s possible that Stewart would never have made the major leagues.

Stewart is aware of the impact that public servants like King and Wilson had on his life. This awareness propelled him, along with his wife Kelli, to create an organization giving other young African-American men in Atlanta similar opportunities. Stewart’s non-profit organization, L.E.A.D. — which stands for Launch, Expose, Advise, Direct — exists to provide young inner-city men in Atlanta opportunities to not only play baseball, but also receive leadership training and networking opportunities, while engaging in service projects. Furthermore, Stewart works to ensure that every L.E.A.D. participant (called “ambassadors”) graduates from high school. This is no small feat, as a 2012 report found that Atlanta Public Schools’ graduation rate was a dismal 52 percent. 100 percent of the young men L.E.A.D. works with graduate from high school. 100 percent of them go on to college. 92 percent of those young men go to college on a scholarship.

Stewart’s reasoning for dedicating a hefty amount of his time to an endeavor that provides no immediate financial return is similar to King’s decision to become the face of the civil rights movement: He felt a burden in his heart to improve the lives of African-Americans. “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy exposes a lot of the problems that we still have in this society. Where there is a problem, there is an opportunity. I have an opportunity so long as I am alive to be a part of the problem or a part of the solution. I want my own legacy,” Stewart explained.

When it comes to fulfilling King’s legacy, Stewart believes that there is still work to be done. “In the African-American community, there is so much division. There is no sense of coming together for the sake of making us better as a community. When I look at photos of King and see photos of him, I see behind him a community of believers. Right now, there is no community of believers. It’s almost like people are racing to be in charge, but unwilling to serve others. People find themselves blessed to be the best, but unwilling to serve the rest. That is what Dr. King did so well. He graduated early and went on to college so he could serve other people. He did not die rich. What he did, was pave the way for other people to be raised up.”

With L.E.A.D., Stewart is working to help other young men in Atlanta rise up from their life’s circumstances. “What we are doing first, is leading them from where they are. We provide consistent programming to help them get to where they need to be. For a lot of the youth we are serving, it is hard for them to set goals, because they don’t know where they need to be. We expose them to promise and hope by allowing them to see, touch and feel opportunities,” Stewart said. Stewart does this not only by introducing the young men to baseball, but by introducing them to leaders of the various Fortune 500 companies based in Atlanta. Furthermore, Stewart is a constant presence at the young mens’ schools, ensuring their progress towards a diploma and volunteering in their classrooms. Finally, he works to instill a burden in their hearts to give back by organizing community service projects for them to complete. “You aren’t a leader if you don’t serve. The service and exposure to what Atlanta has to offer gives them a sense of investment in and belonging to the city of Atlanta,” Stewart noted.

Forty five years after Dr. King’s life was taken on the balcony of a Memphis hotel, his dream lives on. His dream lives on because of the work of people like Stewart, who find enough burden in their heart to dedicate their lives to improving those of others.