Noted psychologist thought leader Dr. Amos Wilson once said, “If you want to understand any problem in America, you need to focus on who profits from that problem, not who suffers from the problem.”

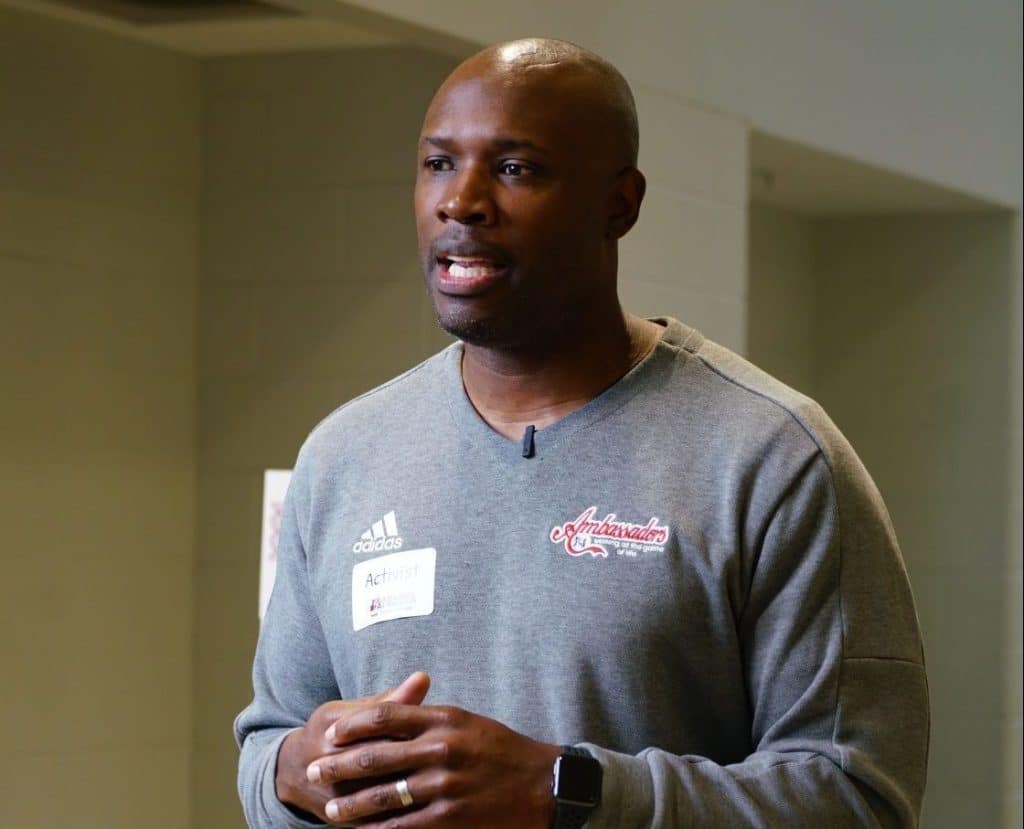

As the Chief Visionary Officer (CVO) of L.E.A.D., Inc. (Launch, Expose, Advise, Direct, www.lead2legacy.org), my focus is on creating a picture of the preferred future for our Ambassadors and organization. I am the blueprint. I am proof that African-American boys born in Atlanta’s inner-city can use the sport of baseball to overcome the “three curveballs” that threaten their success: crime, poverty and racism.

Unfortunately, these threats are big business. My birth city and home, Atlanta, ranks No. 1 in America for racial income inequality. To those outside of Atlanta, we are considered a world-class city—the “Black Mecca.” But if that were even close to being true, LEAD would not have to exist. Racism creates crime and poverty. Racism is a structure, not an event; and it is about power before it is about people. It is about affluence and influence.

Generationally disenfranchising African-American people from quality housing, education, employment and healthcare definitely causes crime because folks ain’t gon’ just not eat, starve to death, not be able to take care of their families, etc. It ain’t gon’ happen.

So why do I say doing the work doesn’t work?

Well, have you ever heard the phrase, “If you build it they will come?”

That has not been my experience on my journey in the non-profit sector .

Like I said earlier, racism is about affluence and influence, and the key to getting your work recognized, sadly, isn’t about doing the best job or achieving the best results.

Philanthropy has an elitist problem.

I believe that and Dr. King’s Letter From The Birmingham Jail states how freedom, equality and citizenship for Black people had an elitist problem, too. I define philanthropy as a way to serve and empower others with financial and in-kind donations. Our donor make-up includes more White donors than African-American donors. The low number of African-American donors hurts me because I know we want to bless people in tremendous ways. We as a people have an abundance of love and prayers and we are wise enough to know that love and prayers alone will not bring about the change we need in our communities. If that were the case, we would have made it to the Promised Land a long time ago.

It takes money to affect the change we need to see—and lots of it.

The truth is that African-Americans cannot give a lot because we don’t have a lot. A close examination of wealth in the US shows staggering evidence of racial disparities. In 2016, the net worth of a typical White family was $171,000—nearly 10 times greater than that of a Black family at $17,150. The city of Atlanta leads the nation in racial income inequality and lack of economic mobility. The median household income for a White family in the city is $83,722, compared to $28,105 for a Black family, according to a report from the AWBI. That’s nearly a 3-to-1 ratio.1 Gaps in wealth between Black and White households reveal the effects of accumulated inequality and discrimination, as well as differences in power and opportunity that can be traced back to this nation’s inception. These gaps in wealth are not equated to the myth that Black people are inferior, lazy and dumb. Though some would like others to believe that.

2The Black-White wealth gap reflects a society that has not and does not afford equality of opportunity to all its citizens. This wealth gap, in fact, demonstrates levels of citizenship where Blacks are second class and Whites are first class, with those who are considered ‘not like those Black people’ and the ‘model minority’ being able to glean benefits from being acceptable and palatable to Whites.

This economic disparity directly ties into the commoditization of crime, poverty and racism in cities like Atlanta:

3 “…the economic disparity, even among African-Americans in this region, is a result of underperforming schools, crime, and White and Black flight from neighborhoods still grappling with the effects of discriminatory housing policies.”

What African-Americans do have often goes to our churches:

4 “Historically, the Black church has been a core institution for African-American philanthropy. The Black church does not only serve as a faith-based house of worship, but it facilitates organized philanthropic efforts including meeting spiritual, psychological, financial, educational, and basic humanitarian needs such as food, housing, and shelter. Black churches are also involved in organizing and providing volunteers to the community and in civil and human rights activism.”

I believe Black churches must do more to serve the African-American community.

My family’s church, Elizabeth Baptist Church (EBC), recently launched a Giving Sunday initiative that raised more than $600,000. Even before our pastor, Dr. Craig Oliver, Sr., created Giving Sunday, EBC has a long history of local missions. In fact, our church is a faithful, generous LEAD donor; providing access to funding, mentors and jobs.

White supremacy is a real thing.

It is a social construct that positions White people at the top of the funnel and African-Americans at the bottom. Well-connected African-Americans in Atlanta play into this by serving as the gatekeepers. They often determine which non-profits will receive funding and which will not.

This is frustrating to me because I serve a lot of families who are constantly in crisis. And I do not have the luxury of playing golf, smoking cigars and sipping wine in order to marginally increase my chances of convincing someone that we are doing lifesaving work in a city that ranks near the top in crime, poverty and racism. My families live in a state of urgency, and so do I.

For several weeks during the initial COVID-19 outbreak, we had to pivot from 90% direct service to youth and 10% outreach, to 90% outreach and 10% direct service to youth. Several of our families could not get help from the large organizations who specialize in food security and housing assistance because their doors were closed at the onset of the pandemic.

LEAD serves 350 African-American boys from Atlanta Public Schools in grades 6th-12th in addition to our alumni. The vast majority of them live in households that could not and cannot afford to shelter in place during a pandemic.

And then, when the medical pandemic clashed with the three social pandemics that Blacks folks have been dealing with forever in Atlanta – crime, poverty and racism – I was disheartened and angered to hear leaders who I respect yell at our neighbors to “go home”. I’m specifically speaking of the protests and riots that took place here after George Floyed was murdered. I stared at the news in disbelief and looked at my wife as she screamed back at the TV – ‘Go home where??!! To these deplorable, drug infested extended stays we’ve been delivering food to? Or to their cars where they’ve been sleeping for months, with their kids??!! The nerve!” What I shared with you was the clean version of what she actually said.

For a city with leaders of such influence and affluence who quote Dr. King all the time, it surprised me that very few – especially Black people – took this moment during the “racial unrest” to stand up and be a voice for poor, Black people in our city. Dr. King did this when he said that rioting is the language of the unheard. Dr. King empathized with rioters because he too understood what it felt like to be unheard and just how very frustrating – maddening even – that can be. Like Dr. King, one of the reasons I do not have to riot and loot is because I have the affluence and influence not to. I believe a lot of the rioters and looters who were being yelled at during the turbulent summer of 2020 represent some of the most vulnerable and disenfranchised people in our city. Hell, most of them didn’t have a home to go to in this ultra-gentrified city—one that has discarded them.

I believe grassroots is where the gold is.

Roots of plants and trees are unseen, but essential. Unfortunately, most grassroots organizations are often obscure and not well-connected. As a result, we are not seen as credible. We often do not have the funds to hire staff to convert our visions to a reality like larger, more well-funded organizations.

The irony is that most big and well-funded organizations started out small. They probably grew because somebody said it was time to financially fuel their mission. And perhaps many of them were not fighting an uphill battle against a city rooted in racism and elitism or they were on the side of racism and elitism and enjoyed the funding that came along with taking that stance.

Grassroots organizations often are faced with the dilemma to change their mission to suit the needs of large donors. But does this demonstrate integrity?

I define integrity as doing the right thing even when it is unpopular. It is only my faith in God that allows me not to compromise my character for a short-term gain.

Faith is a belief that things will happen according to the way God ordains it. Faith is very different from having a vision. Vision is what we believe will happen in the future as a result of us executing on our organization’s mission daily.

Our vision is crystal clear in our minds, but grassroots organizations typically lack the staff and/or funding to hire people to best tell and sell their stories to donors.

If passion paid the bills, grassroots organizations would be the kings and queens of the hill.

So, what would I do with more funding for LEAD? I’m glad you asked. I would execute the work of LEAD according to our vision. Consider this: Today’s African-American youth in Atlanta are over-mentored and under-sponsored. I boldly made this statement on March 28, 2019 at the Commerce Club during Goodwill’s Prosperity For All: Closing Atlanta’s Wealth Gap” event. I made this statement before I asked a question to the panel which included Keith Parker, Mayor Bottoms, Raphael Bostic and Hala Moddelmog. This is the first time anyone has made this declaration, or at least that’s what I gathered from the “mmmms” and gasps from the room. Atlanta businesses must understand that mentorship is not the ceiling, it is the floor.

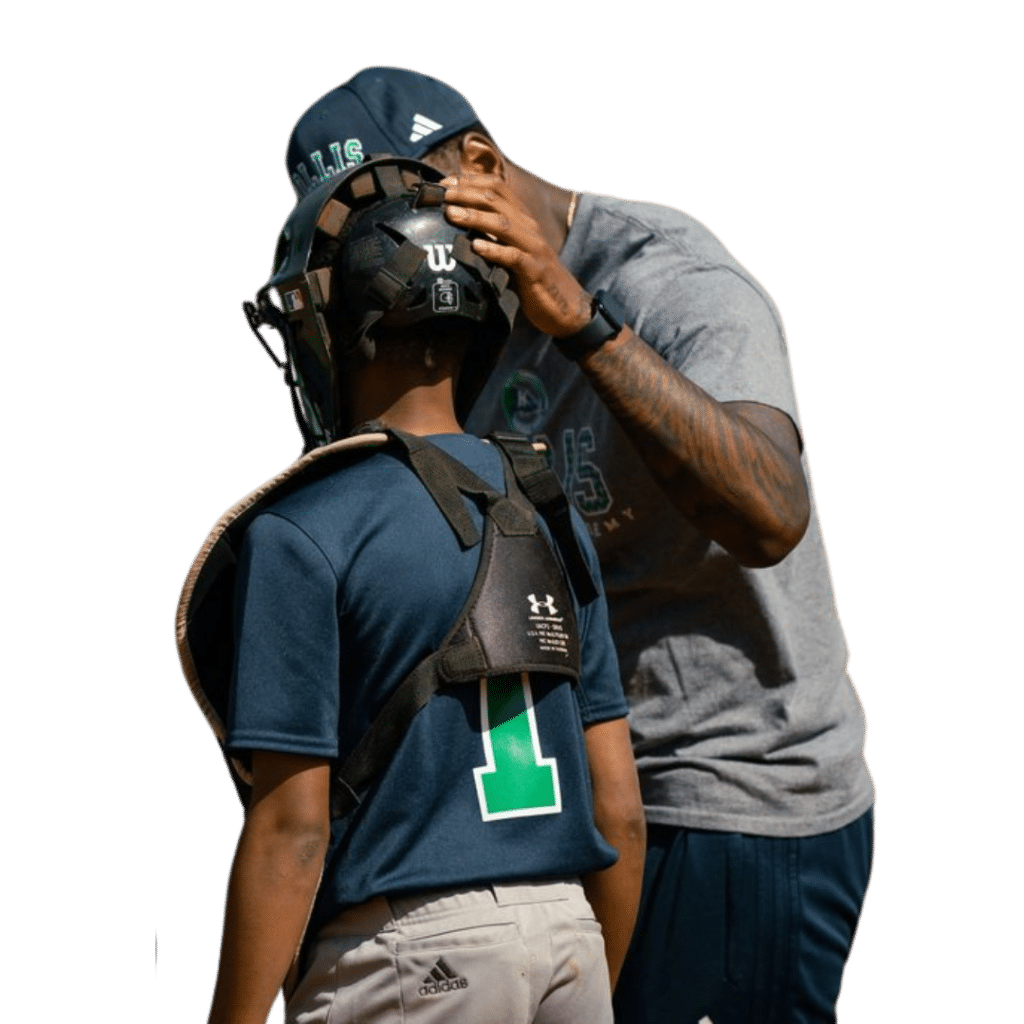

That is where LEAD comes in. LEAD stands for Launch, Expose, Advise, and Direct. It is a methodology. We scout the counted out – Black boys in Atlanta Public Schools from low-income households – and we coach them on how to win at the game of life by using baseball to teach them how to overcome crime, poverty and racism.

While coaching is important, coaching without advocacy for disenfranchised youth in Atlanta is as ineffective as someone trying to drive a car that does not have an engine.

L.E.A.D measures success in the clearest and most simplest of terms: The number of boys and young men (designated as L.E.A.D Ambassadors) who are put on a path that will empower them to lead and transform their community, and overcome the three social pandemics of crime, poverty and racism.

The all-in cost of creating that path—the programming and nurturing that deliver the outcome of an empowered young man—is approximately $5,000 per Ambassador.

As LEAD receives funding, it is allocated to maintain or enhance the quality of its programming while also expanding the quantity of young men who can be included in the programs each year. As an investment in our community’s next generation, the donations LEAD receives provides a maximum positive return based on a clear performance indicator—the measurable success of our Ambassadors.

LEAD Ambassador alums have achieved the following to date: 100% high school graduation rate, 93% college enrollment rate, a 90% college scholarship rate, 19% college graduation rate and about 14% enter the workforce, military or pursue entrepreneurship.

Because the Ambassadors reside in Atlanta communities in which young men have the highest possibility of incarceration, that $5,000 invested each year can be compared to the roughly $100,000 cost to the community to incarcerate a youth, as well as an unknown, but substantial opportunity cost of fewer productive young leaders in the community.

From a purely economic standpoint, this represents at least a 20:1 return on investment to the community and likely much higher.

After over 14 years with both a strong business model and a new facility to operate from, LEAD is now poised to scale from its current 40 high school Ambassadors per year to 100 in the years to come. This initiative is known as Mission:100.

New funding will be directed toward program management resources, which will increase the program dosage at our Jr. Ambassador (middle school) level, and increase the opportunities at the Ambassador (high school) level so that more at-risk boys and young men can be included in our programs each year. And with more support, we’ll be starting our Lady Ambassadors program to include opportunities for girls and young women through tennis. I know ya’ll knew Kelli wasn’t going to leave our girls out of this empowerment movement.

Each investment that LEAD receives means more Ambassadors, more future leaders who inspire those around them to strive and achieve for lives of significance. All of this translates to a direct positive impact upon our community and constitutes our authentic offering of doing what we can to indeed make Atlanta ‘a city too busy to hate’, ‘a city on a hill’, all of those phrases we claim to be, but are truly not – yet.

Photo Credit: India Albritton

1. BizJournals – Economic Disparities in the “Black Mecca”

2. Brookings – Examining the Black-white wealth gap

3. AJC – Atlanta and black wealth: Success for many, but not for all