“I can accept failure, everyone fails at something. But I can’t accept not trying.” — Michael Jordan

“I can accept failure, everyone fails at something. But I can’t accept not trying.” — Michael Jordan

I began paying close attention to Michael Jordan in 1982 because he helped North Carolina win the NCAA National Championship. In 1984, he was the “National Player of the Year,” and was later drafted in the first round by the Chicago Bulls.

I was eight years old in 1984. That was also the year I fell in love with watching baseball. It was the Chicago Cubs games during the hot summers in Atlanta at my grandparent’s house.

Like most kids in the ’80s and ’90s, I wanted to be like Mike. I watched and watched, desperately trying to walk like him and shoot like him. I even tried to chew gum like him.

By 1992, I was able to meet Jordan a few times because my travel baseball coach, Derrick Stafford, was a NBA referee. He knew MJ well.

Like me, Coach Stafford, was born and raised in Zone 1 Atlanta, a majority Black community that was defined by loving, working class people.

Eventually, I had my first professional workout with the Chicago Cubs. It was 1990 and I was 14. I had my mentor, the late T.J. Wilson, to thank for the opportunity. So, by the time I was playing for Coach Stafford, I was completely focused on being drafted at 18.

Coach Stafford was a good man. He loved his players. He was extremely knowledgeable about baseball and was well-connected. The problem I had wrestled with in my head as a 16 year old was that we were Black.

As I have discussed in past blogs, loyalty is showing constant support toward a person or organization. Before racism is about people, it is about power. My experience with baseball at the professional level exposed me to the decision-makers, who were all white men.

Being Black and being white is not the same thing culturally. While we come together as the human race, we are coming together as two distinct groups of people.

At 16, I thought that in addition to playing well on the field, I also had to learn how to act white off the field. Nobody, not even Coach Stafford, could teach me how to do that.

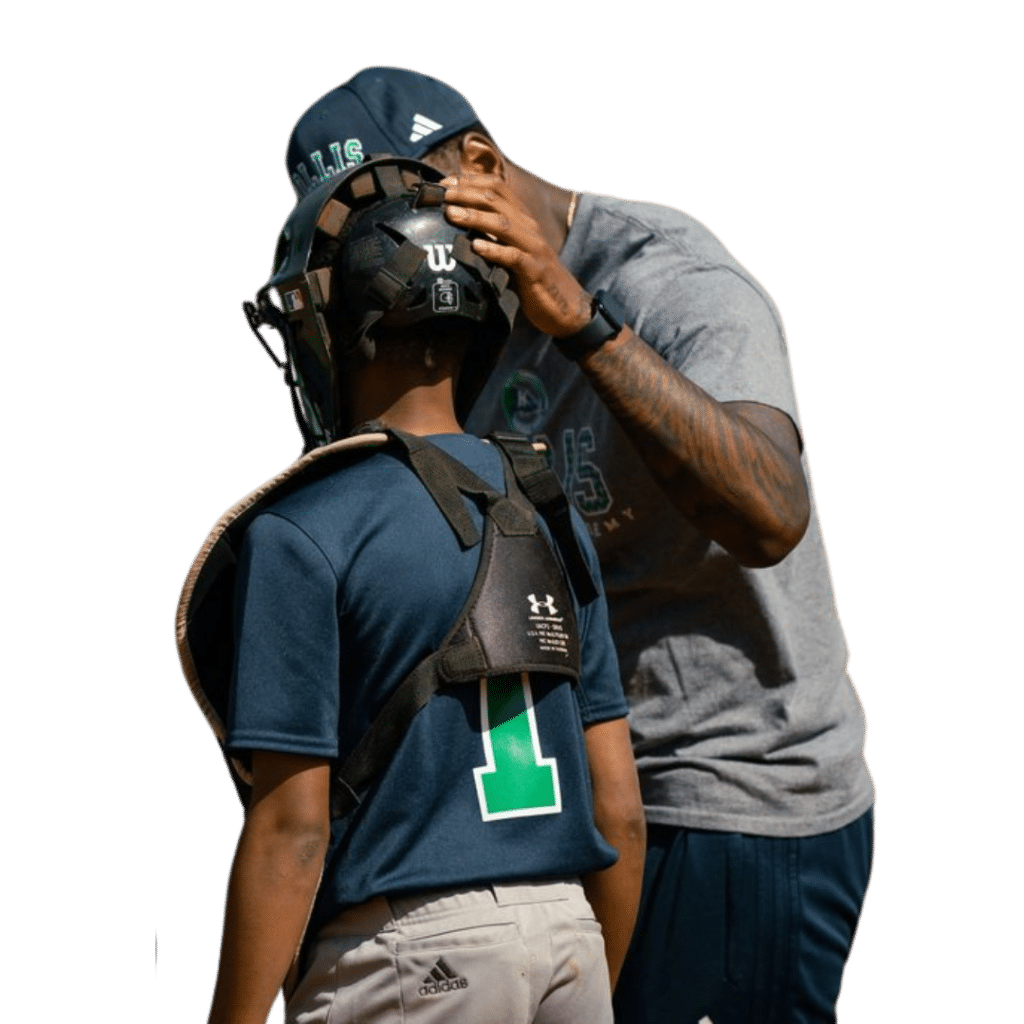

Today, as a 47 year old Black man, I have been blessed to be drafted twice by the Chicago Cubs and played in the Cubs organization for two years. I am a successful coach who has had more than 40 former clients who played at the Major League Baseball level.

In addition, I am in contact with hundreds of Black boys from varying socioeconomic levels on a yearly basis. My experience and my travels have taught me three reasons why Black boys, once like me, still struggle to be loyal to Black-led organizations. The reasons are:

- Tests

- Stress

- Progress

I believe the person who owns the definition owns the movement. So let me define some words before I continue to make my point.

- Struggle is the process of trying to reach a goal while making mistakes out of ignorance

- Stupidity is knowing the right thing to do but not doing it

- Loyalty is showing constant support toward a person or organization

- Organization is an entity comprising one or more people and having a particular purpose

Test is a procedure intended to establish the quality, performance or reliability of something, especially before it is taken into widespread use - Stress is pressure or tension exerted onto something

- Progress is forward or onward movement toward a destination

Taking the test

Trying to be the best requires being tested. There is a difference between practice, play and performance. Practices prepare you to test what you have been working on when you play the game, while performance requires stress to be present.

As it was when I was a teenager, there are still hundreds of thousands of Black boys in America who are not convinced that a Black man can guide them to the Promised Land.

So to deal with the stress of the performance test, White becomes Right.

Stress

Trying to be the best brings stress. My mentor, Skip Nelloms, recently showed me there are two types of stress: eustress and distress.

Eustress is moderate or normal psychological stress and is interpreted as being beneficial. Distress is extreme anxiety, sorrow, or pain and interpreted as being detrimental.

Getting a hit in front of hundreds of baseball scouts can be stressful for sure. For a lot of Black players, the thought of having a white coach vouch for you to white scouts if you strikeout is the best route.

Progress

Trying to be the best requires progress. Less than 8% of Major League Baseball players are African-American. Not only are those numbers low at the MLB level, but we also have low representation in the medical field, Fortune 100 company leadership, homeownership, and the list goes on.

Progress feels good when you are receiving the benefit of doubt, respect and trust.

In my experience, as a teenager as well as today, I do not believe Black people are not afforded these three valuable things outright. These three things are what I call the “it” factor.”

Black people oftentimes have to show and prove we can perform in order to earn “it.” Or, if we have a white coach who says we deserve “it,” we can have “it.”

Baseball is an expensive sport. For young Black boys, it costs financial, emotional and mental currency.

For more than 20 years as a Black man, I have been able to successfully coach Black boys to become Major League Baseball players because I have instilled the following in them:

- Shared experiences

- A proven philosophy and methodology for development

- An understanding of learning and teaching styles

- A trauma informed approach to coaching

- An expertise in race relations

- A proven track record of negotiating MLB Draft signing bonuses

- A strong network of contacts that includes both Black and white executives at the Major League Baseball level, to Black and white college coaches and Black and white recreation to Travel Baseball coaches

I want Black boys to know it can be as safe and rewarding for you to be led by a Black man as it is by a white man.

Whoever leads you into manhood should be able to answer the following 10 questions for you with conviction, clarity and conciseness within 10 minutes. If they can, they will earn the right to coach you.

- Coach, who are you?

- What has happened to you as a coach?

- Where are you going as a coach?

- What do you see in me?

- Why are the participation numbers of African-Americans so low for players and coaches at the collegiate to Major League levels?

- Is there a Black and white way to play baseball?

- Is there a Black and white way to live life?

- Where can I go as a player?

- Where can I go as a person?

- How will you guide and protect me when the going gets tough?

Now is the time to push forward. Now is the time to find your place and the person who can lead you. That person, regardless of color, should be a person who is willing to give you the truth, the opportunities to find the answers and ability to find your way through the successes and failures.

For more information, visit L.E.A.D. Center for Youth today. Also, check out our Digital Magazine.

C.J. Stewart has built a reputation as one of the leading professional hitting instructors in the country. He is a former professional baseball player in the Chicago Cubs organization and has also served as an associate scout for the Cincinnati Reds. As founder and CEO of Diamond Directors Player Development, C.J. has more than 22 years of player development experience and has built an impressive list of clients, including some of the top young prospects in baseball today. If your desire is to change your game for the better, C.J. Stewart has a proven system of development and a track record of success that can work for you.